Cool Invention Shoes Cool Designs Easy Fire

The business of design tends to be project focused. A task is established, and a designer is hired to complete it. Usually a company or organization, with a distinct need, commissions those projects. Ultimately, the world's great designers and architects are known for the work they have completed for others. It's the business-as-usual of design. It's an incredibly rare thing to find designers who instigated their own project.

But why?

It's a question I've asked myself many times. Having spent over ten years working with one of our era's greatest designers and thinkers, Bruce Mau, I was fortunate to be exposed to a revolution in the practice that has shifted our understanding of design as a strictly visual practice to one where the skills of the designer are re-contextualized. Today, design skills are being applied to unconventional problems where conventional problem solving has failed. With Bruce's Massive Change project and now with his Massive Change Network, we're seeing a shift towards a more proactive embrace of self-determination as designers.

The question, though, is why we don't extend this thinking further? Why doesn't our profession more proactively take on projects of our own imagining?

Towards a New Model of Practice

Design is the practice of making something out of nothing. We are educated in the art and science of creating things that people want to own or use. Yet the practice of design is dominated by a legacy of a fee-for-service business model that is restrictive. We end up working on what our clients ask us to work on.

The result is that no design practice has grown to any measure of significant global impact. The world's biggest design firm is IDEO, with about 650 people and annual revenues of about $130 million dollars. Compare that with a "design-driven" company like Apple that makes $130 million dollars–in profit–every day.

So if designers are specialists in creating desirable, wonderful, smart things, then why don't we see more designers doing it on their own? There are some exceptions: Yves Béhar with August Smart Locks among other projects or Scott Wilson with the Lunatik line of accessories. But even their projects tend to be spin-offs of their design studios rather than the design studio itself as the big idea generator.

There may be no easy answer to how to take this kind of control, but we should always be searching for it. In other words, what do you stand for? When it came time to start my own company, Frontier, I founded it on the idea that design by definition contains a sense of intention and purpose and, when conceived in the right way, can be built with a more sustainable and diverse business model that permits a more diverse and purpose-driven practice.

Connect Everything

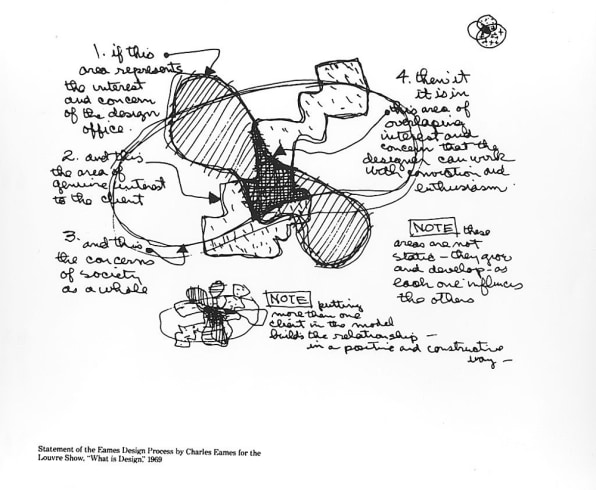

Charles Eames said, "Eventually everything connects–people, ideas, objects, etc….the quality of the connections is the key to quality per se." The Eames office had a diagram that explained their approach to practice. There were three overlapping circles. One represented the interests of the design office. One represented the interests of the client. And one represented the interests of society as a whole. Their work, the Eames said, was at the intersection of the three.

Yet this intersection implied a business model: You needed clients. And those clients would pay you a fee to pursue things that interested them, the design office, and, ideally, society as a whole. The Eames had the luxury of choice. Their talent provided them with opportunities that ensured that the overlap stayed in line with their own interests. But what about the rest of us?

Realistically, we don't always have the luxury of choosing our clients. So how do we shape ourselves in a way that matches our greater ambition? How can we establish a purpose that drives our practice more deeply and lets us work with more self-determination? The Eames' approach is still the best guide for staying on course: first, connect everything in order to understand relationships, influences, and possibilities.

Embrace Complexity and Uncertainty

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan, writes, "Categorizing always produces reduction in true complexity…Any reduction of the world around us can have explosive consequences since it rules out some sources of uncertainty; it drives us to a misunderstanding of the fabric of the world."

Rather than simplify a complex situation, we must start with a certain kind of fearlessness in the face of the unknown and establish tools to help us find answers in the absence of tangible information. And once we embrace that unknown, it's the methodical application of those tools toward solutions that point us in a better direction.

A natural permission dictates the course of most companies. The best companies do one thing and do it well. But what if the one thing you do well is, in the words of the Eames, the process of discovery? As a designer, where do you draw the lines between what you can and cannot do? You don't draw lines. Designers won't be conducting surgery any time soon, but they can conceive of better hospital experiences. The idea is to recognize the frontier, the space of the unknown that remains to be discovered. It's the process of mapping out the possibilities and uncovering the real potential at the edge that allows for true invention.

Forge A Process of Discovery

Richard Saul Wurman, author and TED conference founder, says Charles Eames's approach to his work allowed for that kind of exploration. "Sell your expertise and you have a limited repertoire. Sell your ignorance and you have an unlimited repertoire. He [Eames] was selling his ignorance and his desire to learn about a subject. The journey of not knowing to knowing was his work."

Ignorance may be the wrong way of putting it. Another way to think about it is something I learned working with Bruce by way of Frank Gehry's office: If you want something done in the way that it has always been done then hire an expert; but if you are trying to do something that has never been done before, hire a designer who is working in this new way. It's important to say that not all designers think this way. Many are craftspeople who specialize in making beautiful visual things. But some also know how to conceive of beautiful experiences where the visual is only one part.

A design-centric company is constantly exploring: intellectually, in practice, and in partnership. It's a sustainable platform for these sorts of things. This commitment to exploration is a long-term one, so when it comes to setting your course, it's important to think beyond fees. It's about finding ways to work on what you love without compromising your livelihood. It's about designing the practice of design itself. While it may not be a perfect practice, hopefully it's a better one.

Designers, instead being strictly at the service of others to solve their problems, it's time to think ourselves and our work as a source of invention, exploration, and creation in its own right. That's how we'll break new ground.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3046518/why-designers-must-put-invention-first

0 Response to "Cool Invention Shoes Cool Designs Easy Fire"

Post a Comment